|

| Joan Carlile Portrait of an unknown lady ca. 1650-55 oil on canvas Tate, London |

|

| John Hayls Portrait of a lady and a boy, with figure of Pan ca. 1655-59 oil on canvas Tate, London |

"Mythologising portraits of this kind were more commonly found on the Continent than in Britain. The figure to the left is from Roman mythology, either a satyr or the god Pan, identifiable by his horns and goat's legs and by the pipes in his left hand. Presumably symbolic of the sin of Lust, he is here a rather humorous figure being kept in his place both by the classically attired little boy who holds a bow and arrow and probably represents Cupid, and by the small dog, a symbol of faithfulness. Pan is also being resolutely ignored by the lady herself, in the role of the goddess Venus, who leans against a rock entwined with the ivy that symbolises marital happiness. . . . The theme of a female sitter with a young male relative attired as Cupid was introduced to English art by the Flemish-born Sir Anthony van Dyck. Little is known about Hayls, from whom, between 1666 and 1668, the diarist Samuel Pepys commissioned a number of portraits, of which only his own image survives (National Portrait Gallery). He described the progress of these in his Diary. Although sometimes described as a rival to Sir Peter Lely, Hayls seems to have attracted rather less exalted clients."

|

| Gilbert Soest Portrait of a gentleman with a dog, probably Sir Thomas Tipping ca. 1660 oil on canvas Tate, London |

|

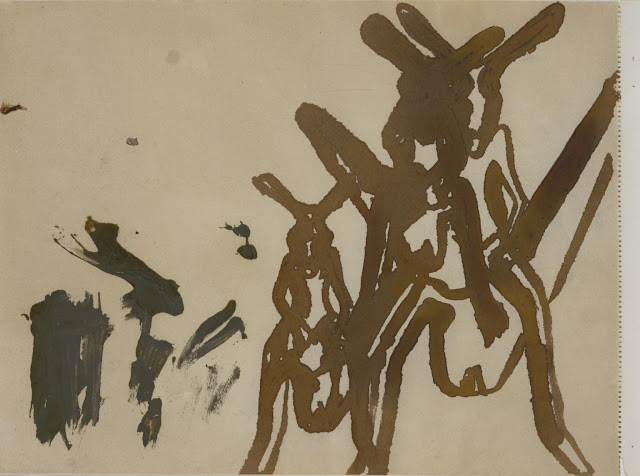

| Mary Beale Portrait sketch in profile of the artist's son, Bartholomew Beale ca. 1660 oil on paper Tate, London |

|

| Peter Lely Portrait of two ladies of the Lake family ca. 1660 oil on canvas Tate, London |

"Sir Peter Lely was born to a Dutch family in Westphalia in 1618. He trained in Haarlem and at the beginning of the 1640s moved to England. In London, Lely had the opportunity to see works by the recently deceased Sir Anthony van Dyck, whose portraiture had transformed the public image of Charles I's court. With the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660, Lely became principal portrait-painter at the court of Charles II. The market for art in Britain at this period was almost entirely for portraits, and Lely increasingly concentrated on that field, absorbing the ideas of van Dyck and adapting his compositions, while lightening and brightening his own palette."

|

| Benedetto Gennari Portrait of Elizabeth Panton, later Lady Arundell of Wardour, as Saint Catherine 1669 oil on canvas Tate, London |

"The sitter, Elizabeth Panton, was the eldest daughter of Colonel Thomas Panton, a member of Charles II's life-guards and foot-guards. Panton's success at gambling enabled him to buy property in Herefordshire and London's west end, where he built what is now Panton Street. In July 1681 Elizabeth, with her mother and brother, left England, claiming health reasons but in actuality to escape the persecution they faced as Roman Catholics. The exiled Catholic court of James II at Saint-Germain-en-Laye in France became a natural focal point for English papists abroad. Gennari followed the Stuart court into exile in 1689, and his notebook records that this was the first work he produced from there. Elizabeth Panton is portrayed, in a statement of her Catholicism, as St. Catherine of Alexandria, holding a martyr's palm and the spiked wheel on which, according to legend, St. Catherine's body was broken. This theme is seen in portraits of Charles II's queen, Catherine of Braganza, some twenty-five years earlier. It was a popular subject with English court sitters, even used by Lely in paintings of Charles's mistress, Barbara, Lady Castlemaine."

|

| Peter Lely Portrait of an unknown woman ca. 1670-75 oil on canvas Tate, London |

|

| Peter Lely Portrait of Elizabeth, Countess of Kildare ca. 1679 oil on canvas Tate, London |

|

| Godfrey Kneller Portrait of John Banckes 1676 oil on canvas Tate, London |

|

| Jacob Huysmans Portrait of a lady as Diana ca. 1674 oil on canvas Tate, London |

"Huysmans frequently painted ladies in the guise of Diana, a presentation that was seen to compliment the beauty, purity and chaste virtue of the sitter. Two other portraits by him show sitters in exactly the same pose as here, holding hunting spears with quivers of arrows at their shoulders, and with the same sharply delineated drapery characteristic of Huysmans. The portrait type was evidently repeated by Huysmans for various sitters, and although possibly influenced by stage costume, had no connection to a specific production. The hounds, one in the shadow on the left, one prominently in the foreground, the nose of another jutting into the picture on the right, suggestive of Diana's hunting pack, are also studio patterns and appear in all three portraits."

|

| John Michael Wright Portrait of Sir Neil O'Neill 1680 oil on canvas Tate, London |

"Sir Neil O'Neill, 2nd Baronet of Killeleagh (c. 1658-1690) is depicted in a richly ornamented costume that would have identified him to contemporaries as an indigenous Irish chieftain. He stands in an open landscape, with a mountain in the distance. At Sir Neil's feet, lower left, lies a closely observed, though incomplete, suit of Japanese armour. It is of a style called 'Do-Maru' meaning 'round the body'; worn during the period c. 1350-1530, it was of a type kept as gifts for eminent people. O'Neill was an uncompromising Roman Catholic, who was to become a Captain of Dragoons in the army of the Catholic British king James II and was to die after fighting at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. The Japanese were perceived in the West as persecutors of Catholics, so the armour may have been included in order to represent O'Neill as a defender of his faith, treading on the deflated armour of its enemies."

|

| Simon Du Bois Portrait of a gentleman, probably Arthur Parsons, MD 1683 oil on canvas Tate, London |

|

| Willem Wissing Portrait of Henrietta and Mary Hyde ca. 1683-85 oil on canvas Tate, London |

"This beautifully balanced work is the portrait of two very important children. Their father was a leading politician, Laurence Hyde, 1st Earl of Rochester (1642-1711), who is presumed to have commissioned the work. Hyde's late sister Anne had been the wife of James, Duke of York, who in 1685 succeeded to the British throne as James II. Thus, the sitters were nieces of the King. By 1705-10 this painting was in the possession of the sitters' cousin, King James's daughter, Queen Anne, and on display at Windsor Castle."

|

| John Riley Portrait of James Sotheby ca. 1690 oil on canvas Tate, London |

– all quoted passages based on notes by curators at the Tate in London