The Perfect Foil is Elizabeth C. Mansfield's new book about forgotten Neoclassical French painter François-André Vincent (1746-1816). He maintained a successful career in France before, during and after the Revolution of 1789, but always in the shadow of the dominant artist of the day, Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). In the publisher's words,

"Art history is haunted by the foil:

the dark star whose diminished luster sets off another’s brilliance.

Relegated to this role by modern historians of Revolutionary-era French

art, François-André Vincent is chiefly viewed in the

reflection of his contemporary, Jacques-Louis David. The Perfect Foil frees Vincent from this distorting mirror."

The jacket image (above) illustrates the story of Arria and Paetus from Roman history. To create it, a graphic designer at University of Minnesota Press transformed one of Vincent's horizontal paintings into a vertical image and added a sort of mirror-contrivance, as if the scene were reflected in water (though in fact it takes place in a prison cell). Paetus, as the author explains, had joined a conspiracy to assassinate the Emperor Claudius. Discovery of the plot led to Paetus's arrest, though his consular rank allowed him to commit suicide rather than face an ignoble execution. On hearing that Paetus was unable to summon the courage to end his life, his wife Arria requested permission to visit him in prison. There, she encouraged Paetus by taking his dagger and plunging it into her own chest before handing it back to him with the famous line,

"It does not hurt, Paetus."

|

| Arria and Paetus (detail), 1784 |

|

| Arria and Paetus (detail), 1784 |

|

| Arria and Paetus (detail), 1784 |

|

| Arria and Paetus (detail), 1784 |

Vincent did paint an alternative version of the same scene, with a vertical composition (but the dust jacket designer obviously did not favor it). The two versions represent two separate moments in the story, like movie stills, as Mansfield points out. The horizontal version (above) shows Arria about to stab herself with her husband's dagger. The vertical version (below) takes place a few seconds later,

after Arria has stabbed herself and is returning the dagger to her appalled husband.

|

| Arria and Paetus, 1785 |

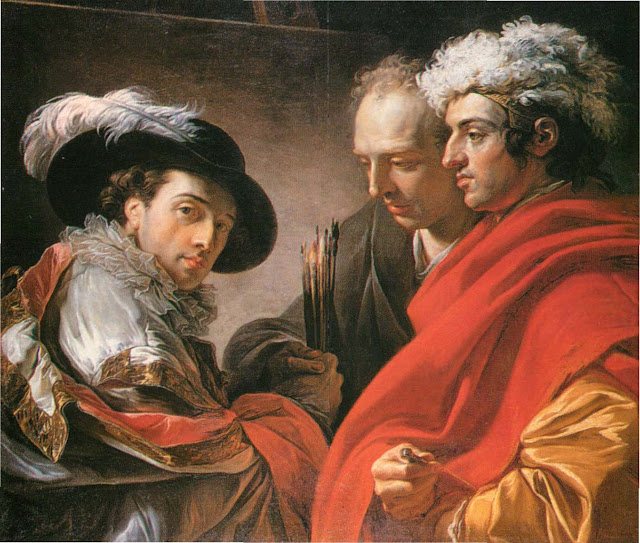

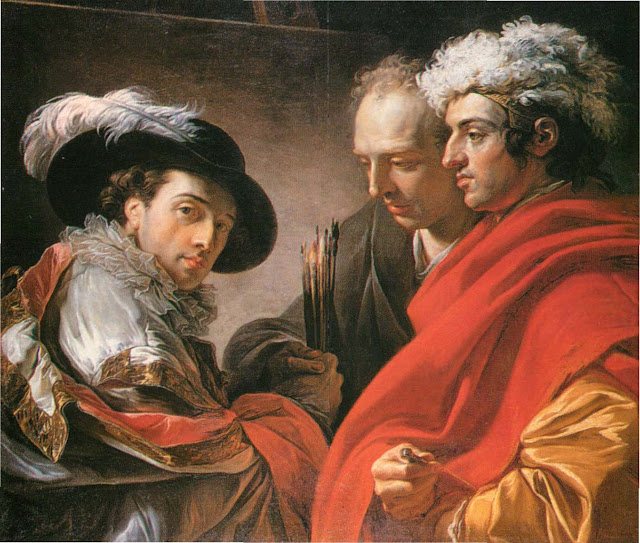

The two paintings were exhibited together at the Salon of 1785. Mansfield makes use of them in building her case that Vincent the painter deserves better than a casual lumping-together with the brilliant Jacques-Louis David. Winning the Prix de Rome (as every French art student aspired to do) enabled Vincent to live and study in Rome from 1771-75. Mansfield reproduces the three half-length compositions below to demonstrate the youthful Vincent's susceptibility to the structural and stylistic influence of

Caravaggio (1571-1610) and

Guercino (1591-1666).

|

| Three Men, 1775 (figure at left is Vincent's self-portrait) |

|

| Belisarius Reduced to Poverty, 1776 |

|

| Alcibiades Receiving the Lessons of Socrates, 1776 |

Vincent also traveled in Italy with the older French painter, Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806). Studies like

The Drawing Lesson (below) show Vincent responding to Fragonard's gentle and traditional Louis XV vocabulary of sentiment. Mansfield suggests that Vincent's unusually wide range of styles contributes even today to his obscurity, because painters of the past, just like living ones, are generally expected to offer a single emphatic "look" – a brand that can be marketed as both unique and consistent.

|

| The Drawing Lesson, 1777 |

|

| Portrait of Vincent by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, 1783 |

|

| Zeuxis Selecting Models from the Most Beautiful Women of Croton, 1789 |

|

| Democritus Among the Abderitans, 1790 |

|

| Portrait of the Baronne de Chalvet-Souvillle, 1793 |

|

| William Tell Overturning the Barque of Gesler, 1795 |

Mansfield devotes most of a chapter to the depiction of William Tell (above) using it as the strongest possible contrast to the manner of Jacques-Louis David.

"Action takes place not in the shallow proscenium articulated in Neoclassical works but in the deep, tunneling space of Baroque painting." She translates and quotes an anonymous French critic of the period who deplored this painting precisely because its Baroque-ness seemed outdated and too blatantly artificial.

"The scene takes place during a storm . . . the wind whips up the waves . . . and yet, everyone is . . . dressed in dry and sparkling clean clothes. It's like an opera. And, what's more, the figures are illuminated by studio lighting."

|

| Portrait of Vincent by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, 1795 |

|

| Study for The Lesson, 1798 |

|

| Study for Battle of the Pyramids, c. 1800 |

Having flourished under the

ancien régime and weathered the chaos of Revolution, François-André Vincent survived to see authoritarianism return with a vengeance under Napoleon. A combination of ill health and disillusionment prevented Vincent from taking up the imagery of Empire to any great extent. Jacques-Louis David, for his part, exploited this new opportunity as happily and ruthlessly as he had exploited every earlier political shift, and soon had transformed himself yet again into the nation's official image-maker.